I have spent the past year-and-a-half identifying, researching, and writing a case study at MIT D-Lab as part of the Local Innovation Group’s research study on inclusive systems innovation. The first of a series highlighting locally-driven systems change, this study focuses on the Letcher County Culture Hub –– a network of organizations in Appalachian Kentucky finding economic empowerment by capitalizing on their collective power and culture. This work informed my history major and concentration in labor economics, as I became interested in how regions become dependent on –– and are decimated by –– mono-economies. We often think of labor as separate from our communities, that we work for someone else somewhere else. This was especially true in Letcher County, where coal companies exploited land and labor to churn a profit, which was often not reinvested in the community. However, residents in Letcher County are generating a “grassroots economy,” transforming social and economic structures and relations in Appalachia.

Prior to my work covering the region, my understanding of Appalachia was constructed by stereotypical narratives. Poverty tours of Appalachia, which have been conducted by journalists and presidents, have reinforced the idea that the region is largely white, poor, uneducated, backwards, lazy, and racist. Books like The Hillbilly Elegy further this monolithic depiction of Appalachia, arguing that success cannot be found in Appalachia, that it is a place one must escape and leave behind. Economic devastation and severe health epidemics are certainly a reality for the region. Residents might be the first to tell you that.

I found it notable how poverty is covered with a lack of empathy in the region –– mainstream usage of words like “hillbilly” and “redneck” have erased the classist roots of these terms. The region is often characterized deterministically –– this poverty and despair is inevitable and inescapable. Progress is unattainable.

That, of course, is untrue, and exactly what my research is trying to challenge.

The Letcher County Culture Hub, the focus of my work, is a grassroots organization whose mission is to take ownership and agency over their economy and their narratives. Their work is deeply radical, but it is rooted in a progressive tradition which has existed in Appalachia since the late nineteenth century. Stereotypes are dangerous because they do not evolve. What I’ve carried from my research –– and what I hope you might gain from reading the study –– is a more nuanced and evolved perspective of Appalachia as an agent of change.

How I got here

I joined the Local Innovation Group in February of 2020 after sending an earnest cold-email to my now-supervisor, Research Scientist Elizabeth Hoffecker. Having worked for a nonprofit organization throughout high school, I wanted to explore how internally-led processes of change differ –– and might be more effective –- than externally-led processes of change.

We’re publishing a series of case studies highlighting local innovation and innovators across the world. These case studies, like the one focusing on the Letcher County Culture Hub, are designed to be teaching tools for other innovators to learn from and potentially replicate. The studies are employing accessible language so other communities (not just academics) can access this research and work. This democratization of knowledge also appealed to me. Given the proliferation of research on foreign groups and nonprofits’ successes and failures in their interventions with local communities, we want to create literature promoting the agency and capabilities of local communities to innovate among themselves.

I joined the group just days before we were sent home as a result of the pandemic, so all of my research has been done remotely through the internet, phone calls, and Zoom. I spent the summer after my first year identifying and vetting potential cases that could be included in the series, which is how I found out about the Letcher County Culture Hub. Through fervent Google searches, I received background information on the Hub as well as the contact information of local stakeholders we could interview. Under Elizabeth’s supervision, I created interview protocols and conducted interviews; did qualitative data analysis; and wrote and edited the case study.

Before and after the innovation of the Letcher County Culture Hub

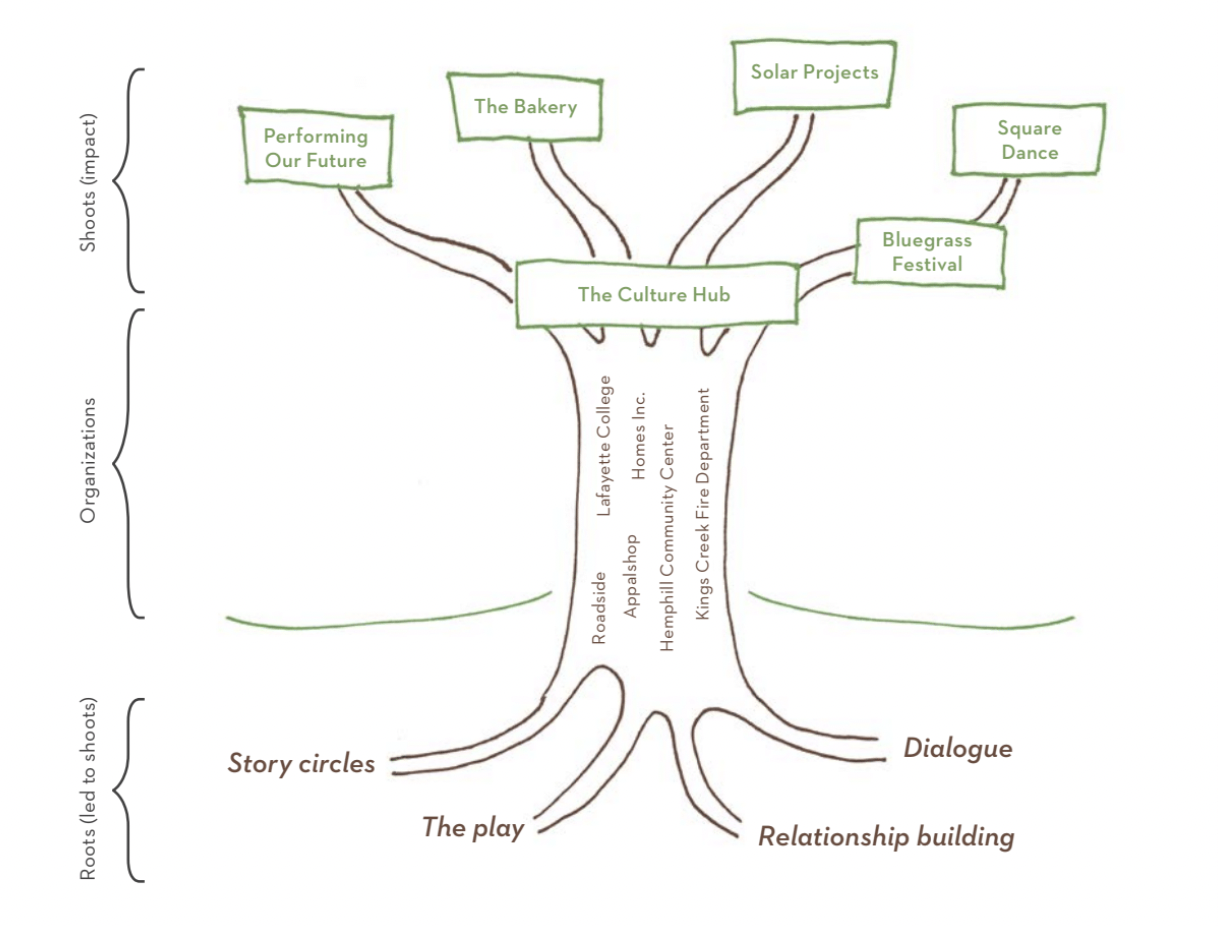

Appalachian Kentucky was dependent on a mono-economy, subsisting on only coal as a commodity. Local entrepreneurship was squashed before it had a chance to exist, because outside interests took precedence over local community issues. Local economist Fluney Hutchinson coined the term culture hub to describe a network of organizations that can catalyze a community’s ability to recognize latent assets and turn them into community wealth. This was eventually actualized with the assistance of grants from Artplace in America and the National Endowment for the Arts. Its social structure (or relationship-infrastructure) generates projects that the community creates, which in turn, creates formalized infrastructure.

The Hub is guided by the principle of “we own what we make” –– creating an inclusive economy and culture for the community by the community. The model involves creating “community centers of power,” a physical space that anyone in the community can access. Organizations require an “opposition-ness” within a Culture Hub, which recognizes that individuals and organizations stand in opposition to the status quo, because that will lead to real change. While the coal economy is the kind of development that relies on telling people to “sit down and shut up,” the Hub is transitioning from one type of culture to another type of culture, one which fosters more community and inclusivity.

The root-to-shoot model explains this process of locally-driven innovation. Despite its formalized structure, the Hub is not separate from the community or engaging the community –– it is made up of community members who are active participants in shaping decisions and policy that will influence their own lives. There is an intentional lack of hierarchy so you won’t find a president or a vice-president. Leadership exists solely to push forward projects. Decisions are made democratically among representatives from each of the 18 community organizations –– including the fire station, local businesses, and community centers.

So what have they done? Dialoguing has created this relationship-infrastructure, which was weakened by the coal industry’s presence. People once competed rather than collaborated, and the Hub changed this by creating productive dialogue across differences. Story Circles is one method which has created a stronger community through dialogue. Story Circles are centered around a prompt –– for example, raising a child that is not your own; people are invited and the circle is volunteer-based. This is an exercise in intentional listening; people are supposed to focus on and critically engage with the storyteller’s story rather than their own.

Local entrepreneurship has also thrived under the Hub. The Blacksheep Bakery, complete with a brick pizza oven, was funded by the Hub. The bakery has an inclusive labor structure, solely employing recovering addicts who were recently incarcerated. Sources of revenue were generated through the Fire Department revitalizing a bluegrass festival, and the community center reviving the square dance central to the community. The Hub’s biggest tangible accomplishment is the Solar Project, which was only initiated with the support of coal miners who okayed the project. The Solar Project is currently finished and running at the local housing authority, HOMES Inc., the Community Center, and the arts collective Appalshop.

Representing Appalachia

The Hub’s work subverts all mainstream narratives about Appalachia. Evolution isn’t considered within the context of Appalachia. I never expected this sort of work in a region I had deemed so conservative. And these stories really surprised me. After the coal economy was decimated, states are turning to private prisons as a potential new source of revenue for these communities. But people in Letcher County refused to go along with a proposal to build a prison in their community. These workers put people over profit, and successfully stopped construction of the prison. In the words of one resident, “I refuse to have our community’s future built on the backs of other people.”

I was also amazed how coal miners took part in pushing solar forward in the region. I’d never considered how communities in Appalachia are building a future, when traditional narratives painted it as a place destroyed and made stagnant by its past. Radical action is greeted with hostility in the United States, and I think I was beginning to lose hope that change could occur in a politically divided country. I was limited in my understanding of progress, thinking that it could only be achieved through federal policy and civic action. Yet this work gave me hope, showed me other ways of catalyzing change. Community members responded to a traditional and ineffectual infrastructure and created a more progressive model suited to the community’s needs.

My interviews with stakeholders, or people in the region, contextualized political differences in a way that no past experience has. I’ve been in bubbles all of my life –– urban bubbles, politically left-leaning bubbles, higher-education bubbles. My research has allowed me to meet people I couldn’t have otherwise met due to sheer physical –– and therefore ideological –– proximity. And I’m not concluding the problem is the liberal elite, but rather that all I’ve known and might have ever known are people like the liberal elite. I was afraid to interview some of these people because I didn’t know what to expect –– would they be racist, suspicious, rude?

And with my first interactions, my preconceived notions were totally obliterated.

One of the key organizers in the Hub is a black woman –– Tiffany Turner –– who spoke about how the Hub’s work is “not so much about defining or redefining who we are, as about “revealing who we are behind the stereotype.” The Culture Hub Lead Organizer, Annie-Jane Cotten, included their pronouns as she/they in her email signature. I met Gwen Johnson, owner of Blacksheep Bakery, and she told me that she refused to take down her Black Lives Matter sign, which proudly stood in the front lawn, and she would frequently engage with community members on Facebook in defense of the movement. These are not instances of virtue-signaling because, frankly, many members of the community do not accept these as normative values quite yet. But my shock was a sign that I was underestimating a population’s ability to forge their own stories and opinions.

There were also people I met with whom I totally disagreed. Bill Meade, the local fire chief, a huge Trump supporter, and a proponent of coal is one example. He disagrees with many people’s politics in the Hub, but remains a part of the organization. My conversation with Bill, however, made me realize that in this region, those who supported Trump may not have done so out of hatred or apathy but out of frustration and disillusionment towards political systems. And this is how someone so conservative like Bill, and a self-declared communist like Ben Fink, can get along and create something together. The Hub’s strength is dialoguing and focusing on local issues. They know that external interests like national politics do not serve, but rather divide, their community.

Class solidarity is often inhibited by national politics because of its entanglement with corporate interests. It is also inhibited by racial divisions, often imposed by employers seeking to disenfranchise their employees. The Hub’s work showed me that perhaps we should recenter what is important by focusing on local issues and working outside of politics.

What I’ve learned from my research

My research has definitely informed most, if not all, of my academic interests. The Hub is working to push forward narrative ownership, which as a History major, excites me. Who gets to tell a story? How can people tell their own stories? How do these stories become accessible to larger audiences? These are questions that I’m still grappling with. I also wonder if there is a way to balance national political interests and local ones. I think the answer is yes, but corporations and profit won’t be compatible with that goal. I hope to continue studying labor rights and worker-owned entrepreneurship. I want to look into how communities recover from externally-imposed mono-cultural economies and begin working for themselves. I want to continue to study –– and advocate for –– Appalachian labor history as a force for change.

My research allowed me to gain an understanding of people’s backgrounds and recognize the power of the people in a region I had always thought was disempowered. Today, this work is happening across the nation –– the Hub is sowing partnerships with urban and rural allies in Uniontown, Alabama, Western Baltimore, and Milwaukee. I’m writing this because I learned something revolutionary, which, in a sentence, can change how a story is told, how a world is imagined.

There is radical work happening today in Appalachia.

About the author

Ahalya Ramgopal (she/they) is an undergraduate research assistant with the Local Innovation Group, where she is supporting the Inclusive Systems Innovation project by conducting research on local innovators. She's currently a third-year at Wellesley College studying history with a concentration in political economy; she is particularly interested in the evolution of the global economic order, and its relationship to labor, state, and corporate power. She hopes to translate her interest in social welfare, economic justice, and labor rights into a future career in policy or law.

More information

Publication: Reviving a Local Economy by Rebuilding Relationships: The Story of the Letcher County Culture Hub

Contact

Elizabeth Hoffecker, MIT D-Lab Affiliated Research Scientist