Bridging academic theory with real-world application

In an inspiring journey that bridges academic theory with real-world application, a dedicated team of students from the MIT D-Lab class D-Lab: Gender and Development embarked on immersive fieldwork in Santa Rita, Colombia. This initiative was not just an academic endeavor; it was a mission to connect, understand, and empower. After a rigorous semester delving deep into gender theory, our objective was clear: to engage directly with the remarkable women miners of Santa Rita, who work in the artisanal gold mines that dot the landscape.

Exploring an intricate web of systemic oppression

Marilyn Frye compares the oppression of women to the situation of a bird in a cage. "A woman can become caught in a bind where, no matter what she chooses to think, say, or do, a bar puts difficulties in her path" (Frye, Oppression). We used Frye's evocative Birdcage Theory as a backdrop to the workshop we offered, in which we explored the intricate web of systemic oppression through the personal narratives of the participants.

Our starting point was a simple yet profound reflection on the daily routines of the women present, aiming to peel back the layers of their everyday lives with open-ended inquiries. This initial conversation laid the groundwork for a deeper, more introspective exercise: identifying the daily challenges each woman faced and yearning to change. By sharing these experiences within intimate breakout groups before bringing them to the larger collective, the participants were not just heard but deeply understood. These personal hurdles, now shared and acknowledged, paved the way for the heart of our workshop: a focused exploration of collective action. This methodology didn't just spotlight the challenges at hand; it wove them into the very fabric of our discussion, ensuring that our collective examination of systemic oppression was not only relevant but profoundly resonant with every participant.

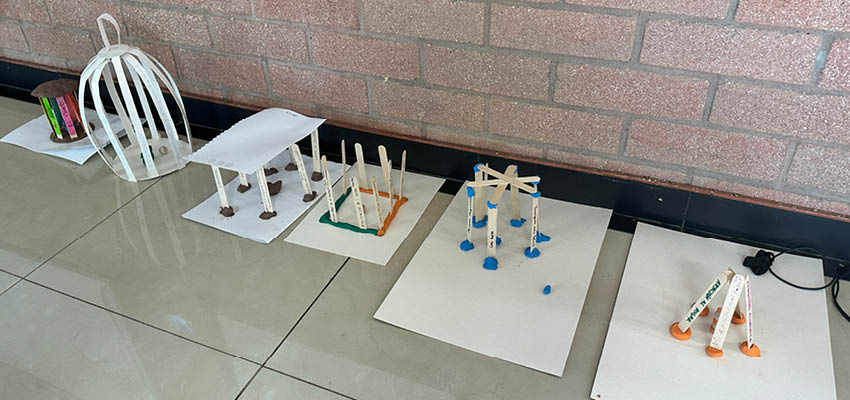

Following the initial reflections, we introduced a metaphorical exercise to deepen the participants' engagement. We invited them to envision the challenges they had identified as birds trapped within a cage, prompting them to ponder the nature of the bars—the specific constraints—that hindered their freedom. To aid in visualization and foster a hands-on understanding, we provided materials like clay, papers, stationery, wooden sticks, etc. for the women to construct physical representations of these birdcages. This creative task was met with enthusiasm, leading to the creation of uniquely crafted birdcages. On the bars of these cages, the participants inscribed the obstacles they faced, an exercise that revealed the shared and systemic nature of many of these barriers.

Facilitators played a key role in steering the conversations within each group, fostering an environment where the co-creation of these bird cages could flourish. This process allowed for a tangible representation of the daily hurdles faced by the participants. Women brought their birdcages to life in three dimensions. This artistic endeavor not only deepened our grasp of the Birdcage Theory but also highlighted the varied methods of expression chosen by the women, reflecting the individuality of their experiences and struggles.

Birdcages

Six groups unveiled their diverse interpretations of "birdcages," covering a spectrum of challenges such as gender and workplace discrimination, the quest for work-life harmony, security concerns in mining environments, and the burden of additional household responsibilities. From these shared insights, we distilled four primary categories of constraints symbolized by the birdcages crafted by the women miners: economic, social, medical, and governmental.

This hands-on methodology proved to be a potent tool for engaging the women in a meaningful exploration of their lives, transcending the limitations of purely theoretical discourse. The act of physically creating and then sharing their birdcages served as a powerful conduit for dialogue. During one such exchange, a participant named Fandina gestured toward her crafted cage and remarked, "We need to find a door." Her succinct statement encapsulates a profound collective yearning among the women miners to alter their current state and ardently pursue avenues for liberation from their adversities. Fandina's words echo a deep-seated resolve to navigate through and beyond the constraints, symbolizing a universal quest for freedom and empowerment.

One participant also had a baby bird in the cage expressing the generational nature of these systemic barriers. In the overlooked and shadowed corners of Santa Rita, Colombia, women miners labor tirelessly, their efforts mirroring those of their male counterparts as they sift through mud, silt, and rocks in pursuit of gold. Their work, both within the confines of the mines and beyond into the realm of domestic responsibilities, epitomizes a struggle not isolated to the mines but intertwined with the fabric of daily life in a community marked by male-dominated structures, poverty, and economic marginalization.

They dream of launching small enterprises, diversifying their sources of income away from the precariousness of gold mining, securing quality education for their children, and achieving a healthier lifestyle for themselves and their families. It is against this backdrop of daily adversities and personal dreams that the necessity of addressing systemic barriers becomes starkly evident. These barriers not only confine women to restrictive roles but also stifle their creativity and economic independence.

Envisioning a world with more agency and choice

The workshop successfully guided the women miners through a process of recognizing systemic and gendered impediments, sharing aspirations and sources of joy, and envisioning a world where they have more agency and choices. The ultimate goal was to empower them to take ownership of their narratives, emboldening them to pursue actions that could facilitate their liberation from the metaphorical cage that binds them. By fostering a culture of profound self-reflection, embracing innovative forms of expression, and taking a long-term perspective on life, the participants were encouraged to identify and dismantle barriers to social cohesion, economic autonomy, and collective well-being.

It effectively identified and articulated the problems through the creation of birdcages, but there appeared to be less emphasis on developing actionable strategies for overcoming these barriers. Fandina's poignant statement, "We need to find a door," underscored the desire for solutions, indicating that future workshops could benefit from dedicating more time to brainstorming and co-designing practical steps toward liberation from these metaphorical cages. Our focus on identifying challenges was crucial, yet the narrative suggests a missed opportunity for establishing a follow-up mechanism to track progress on the action plans and solutions. Incorporating a structured follow-up could help in assessing the efficacy of the strategies devised during the workshop and provide ongoing support to the participants.

Looking ahead: moving from awareness to action

As we reflect on the journey of our workshop, it becomes clear that while strides were made in illuminating the systemic constraints faced by the women miners of Santa Rita through the lens of the Birdcage Theory, there remains a path to be tread towards achieving tangible change. The workshop illuminated the power of collective reflection and creative expression in identifying challenges. Yet, the poignant reminder from Fandina, seeking a "door" out of her cage, underscores a critical area for growth: transitioning from recognition to action. This experience has laid a foundation upon which future workshops can build, emphasizing the need for nuanced understanding, actionable solutions, and sustained engagement. By refining our approach to more directly address the complexities of the participants' lives and focusing on empowering them with practical strategies for change, we can move closer to unlocking those doors to freedom. The journey of the women miners of Santa Rita, rich in aspiration and resilience, inspires us to envision a framework of workshops that not only map the cages but also, and more importantly, forge the keys to open them.

About the authors

- Pragun Aggarwal: Harvard Kennedy School, Class of 2024, Master in Public Policy

- Yulu Gu: Wellesley College, Class of 2024, Economics & Philosophy

- Ishu Gupta: Harvard Kennedy School, Class of 2024, Master in Public Policy

- Diksha Kataria: Harvard Kennedy School, Class of 2024, Master in Public Policy

- Jyoti Sharma: Harvard Kennedy School, Class of 2024, Master in Public Administration

More information

MIT D-Lab class: D-Lab: Gender and Development

Contact

Libby McDonald, MIT D-Lab Lecturer and Associate Director for Practice